Intro

The Black Panther Party for Defense, A.K.A. The Black Panther, was founded in 1966 by by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale in Oakland California.

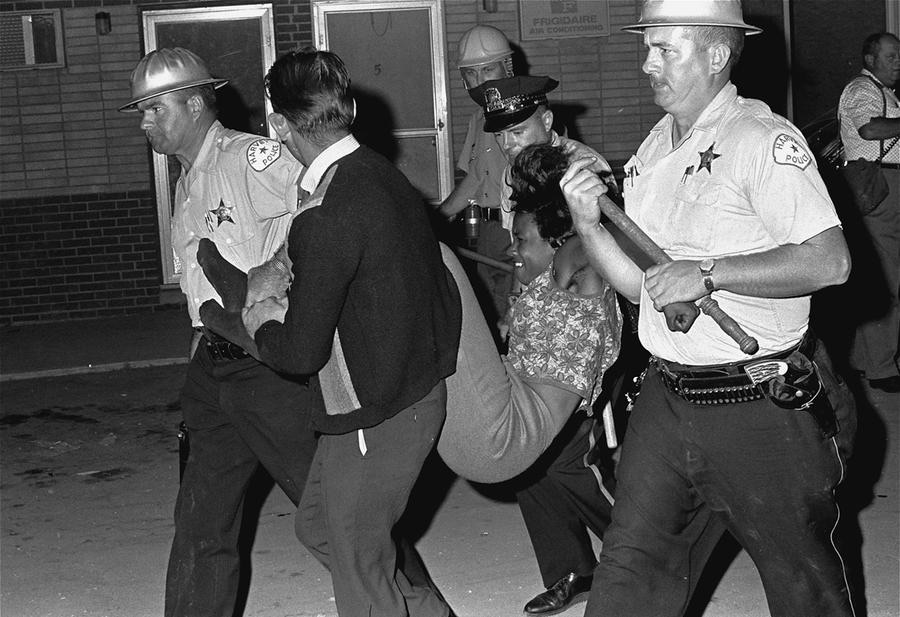

In the wake of Malcolm X's assassination in 1965, the African American communities across the US were in riots. All the years of work and protesting they had done, felt pointless. With all the heroes of the Civil Rights Movement fading away, cities were in shambles, and the Black Population still suffered from immense political and social inequality. Such troubles led to riots such as the Watts riots in Los Angeles, among many others. Police systems started using brutality as a form to contain the crowds. This gave white officers confidence to apply the same force on simple African American crimes, and led to the normalization of such.

In the wake of Malcolm X's assassination in 1965, the African American communities across the US were in riots. All the years of work and protesting they had done, felt pointless. With all the heroes of the Civil Rights Movement fading away, cities were in shambles, and the Black Population still suffered from immense political and social inequality. Such troubles led to riots such as the Watts riots in Los Angeles, among many others. Police systems started using brutality as a form to contain the crowds. This gave white officers confidence to apply the same force on simple African American crimes, and led to the normalization of such.

the start

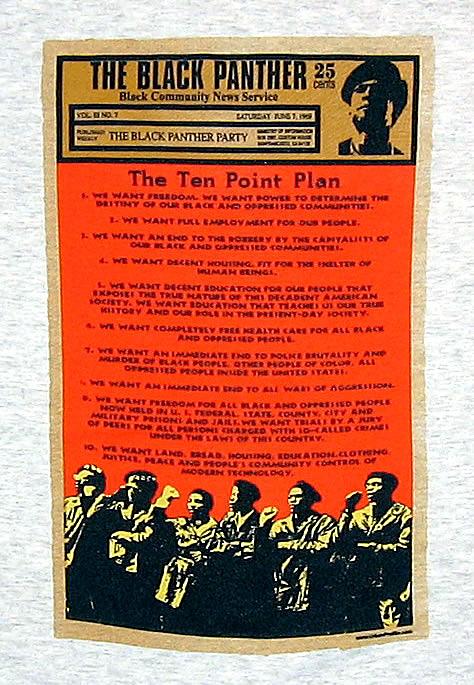

Watching everything occur around them, Merritt Junior College students Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale knew something had to happen. Newton and Seale met in 1965 at Merritt College where they were exposed to a wave of Black Nationalism. Taking this inspiration, they created the Ten Point Plan in order to combat the inequality that they witnessed within Oakland.

The Ten-Point plan consisted of two sections: The first, titled "What We Want Now!" described what the Black Panther Party wants from what they would describe as the racist leaders of American Society. The second section, titled "What We Believe," outlines the philosophical views of the party and the rights that African Americans should have, but are denied.

The main points of the platform were that the Black Panther Party believed that they should be able to choose their own destiny, that every man should be employed by the government to be able to support himself and his family, and that no black man should serve in any military branch.

The Black Panther Party refused to fight for a government that does not treat them as full citizens of the United States of America. The Black Panther Party may have seemed like they were revolting against America, but were only doing what they felt was right. A major difference between the Black Panther Party and other black nationalist groups was intent. Black Panthers rooted for justice of African Americans, and wanted nothing more.

The Ten-Point plan consisted of two sections: The first, titled "What We Want Now!" described what the Black Panther Party wants from what they would describe as the racist leaders of American Society. The second section, titled "What We Believe," outlines the philosophical views of the party and the rights that African Americans should have, but are denied.

The main points of the platform were that the Black Panther Party believed that they should be able to choose their own destiny, that every man should be employed by the government to be able to support himself and his family, and that no black man should serve in any military branch.

The Black Panther Party refused to fight for a government that does not treat them as full citizens of the United States of America. The Black Panther Party may have seemed like they were revolting against America, but were only doing what they felt was right. A major difference between the Black Panther Party and other black nationalist groups was intent. Black Panthers rooted for justice of African Americans, and wanted nothing more.

impact

From there, the party set out with their plan for justice.

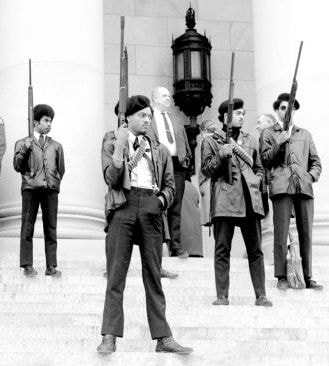

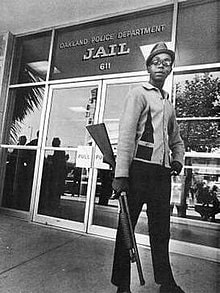

The Party was most well known for their Police Surveillance Groups. They organized armed patrols that followed the police around the black community. On these patrols they wore leather jackets and berets as uniforms to signify the military discipline of the Panthers as well as a new black power identity. They were legally allowed to carry guns in hand at the time, so the White police officers couldn't do anything to charge them.

This was pretty effective at the time, and created a safer environment for the African American community.

The Party was most well known for their Police Surveillance Groups. They organized armed patrols that followed the police around the black community. On these patrols they wore leather jackets and berets as uniforms to signify the military discipline of the Panthers as well as a new black power identity. They were legally allowed to carry guns in hand at the time, so the White police officers couldn't do anything to charge them.

This was pretty effective at the time, and created a safer environment for the African American community.

|

Once the Nation saw the power that the Party had, the Black Panther Party started spreading to bigger cities and grew in population. By 1970, the BPP had over 30 national chapters in major cities including Los Angeles, Chicago, Illinois, New York, and Seattle, Washington.

The Black Panther Party made significant social impacts. contributions The Black Panther Party found ways to spread their messages and ideas across to the citizens of America; such as: its newspaper, The Black Panther, mass rallies, speaking tours, slogans, posters, leaflets, cartoons, buttons, symbols: like the fist, graffiti, political trials, and even funerals. Their work eventually was broadcasted on TV programs, and had regular sections in newspapers.

The Black Panther Party made significant social impacts. contributions The Black Panther Party found ways to spread their messages and ideas across to the citizens of America; such as: its newspaper, The Black Panther, mass rallies, speaking tours, slogans, posters, leaflets, cartoons, buttons, symbols: like the fist, graffiti, political trials, and even funerals. Their work eventually was broadcasted on TV programs, and had regular sections in newspapers.

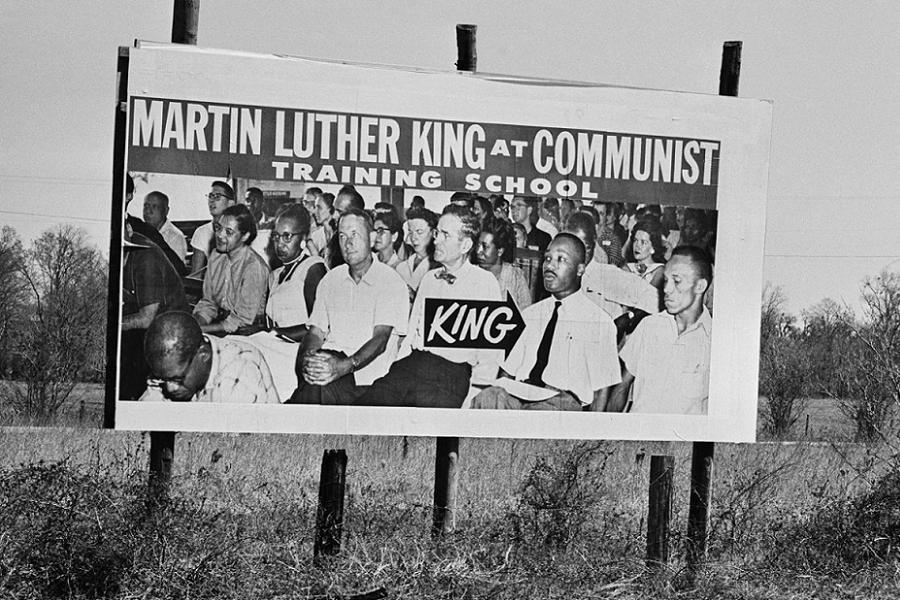

But there was only one problem in their plan. The problem was J. Edgar Hoover–director of the FBI. Hoover saw the Black Panthers as a threat to the American Government as a whole. While J. Edgar Hoover was destroying the Black Panther Party for the safety of white Americans, and was destroying the lives of black Americans. The US Government was starting to feel the power of the Group, and felt the need for something to be done. Hoover, in August of 1967 began a counter-intelligence program (COINTELPRO) to “neutralize” the Black Panthers and other “Black Nationalist Hate Groups.”

Hoover tried to used tactics such as spreading false propaganda and harassment to take down the group. The goal was to make the White population believe that their intent was to harm, instead of what they were actually doing–helping the community that wasn't helped enough.

Hoover tried to used tactics such as spreading false propaganda and harassment to take down the group. The goal was to make the White population believe that their intent was to harm, instead of what they were actually doing–helping the community that wasn't helped enough.

*COINTELPRO started in early 60s, but was more often used in the late 60-early 70s.

CITATION SOURCES

Primary Sources

– “Black Panther Party giving free food, shoes at rally”. 1972, April 15. New York Amsterdam News, p. D8.

- “Militants Occupy Columbia School: Reparations Demanded for Black Panther Party”. 1970, March 14. New York Times, p. 35.

Secondary Sources

- Jeffrey, James. “Shedding New Light on the (Real) Black Panthers.” BBC News, BBC, 1 Apr. 2018, www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-43587976.

- Barbian, Elizabeth, et al. “WHAT WE DON'T LEARN ABOUT THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY — BUT SHOULD.” Rethinking Schools, www.rethinkingschools.org/articles/what-we-don-t-learn-about-the-black-panther-party-but-should.

- “COINTELPRO.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 18 Oct. 2019, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/COINTELPRO.

Primary Sources

– “Black Panther Party giving free food, shoes at rally”. 1972, April 15. New York Amsterdam News, p. D8.

- “Militants Occupy Columbia School: Reparations Demanded for Black Panther Party”. 1970, March 14. New York Times, p. 35.

Secondary Sources

- Jeffrey, James. “Shedding New Light on the (Real) Black Panthers.” BBC News, BBC, 1 Apr. 2018, www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-43587976.

- Barbian, Elizabeth, et al. “WHAT WE DON'T LEARN ABOUT THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY — BUT SHOULD.” Rethinking Schools, www.rethinkingschools.org/articles/what-we-don-t-learn-about-the-black-panther-party-but-should.

- “COINTELPRO.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 18 Oct. 2019, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/COINTELPRO.